The vessel is an ancient form in which we find the principles of both containment and protection – two of the fundamentals of life. Premature fracture of many fragile protective shells or membranes means almost immediate death or destruction. On the other hand, a cleavage at the right moment may signify life liberating itself or an idea or thought breaking forth and materializing itself in creativity. (GJERTRUD HALS)

I am honoured to present ULTIMA, the first solo exhibition in France by contemporary artist Gjertrud Hals. Born in 1948 on the northwest coast of Norway, Gjertrud Hals is considered an important pioneer in the field of Scandinavian fiber art. She has been one of the redefining figures of textile art by liberating the material from the loom and displaying it in space as three-dimensional sculpture. Her international breakthrough came in the mid-1980’s with LAVA, a series of large urns made of cotton and flax pulp that marked her transition from textile to sculptural fiber art. In 1987, she was granted First Prize in the Metro Arts International Art Competition in New York, followed by the Grand Prix in the Kyoto International Textile Competition in 1989. Her works have been acquired by important private and public collections, such as the National Museum of Contemporary Art in Oslo, the Museum of Contemporary Crafts in New York, the Museum of Decorative Arts in Lausanne and the Bellerive Museum in Zürich.

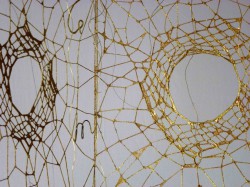

The title of the present exhibition – ULTIMA – is derived from Gjertrud Hals’ ample eponymous vessels, delicately knitted from cotton and linen threads and hardened with resin. These one-meter tall, featherweight vessels hardly touch the ground. Their size and their lightness contradict each other in certain ways. They seem to levitate and appear almost like a vision. Their ambiguous presence is further enhanced by their incapacity to contain anything (other than themselves) due to their soft, perforated structure. They are self-contained so to speak. Yet, in spite of their delicate transparency they convey a feeling of quiet strength.

The shell form of the ULTIMA pieces is central to Gjertrud Hals’ art. In the words of curator Tove Lande…”For Gjertrud Hals, the shell is both an ideogram and an archetypal symbol. She prefers to use dense symbols that may encompass several meanings, and for her the shell is precisely that type of symbol. On the one hand, it represents the protective membrane between life and death; on the other hand, it is a symbol of the jar or vessel. In addition, the shape strongly reminds her of the shells she used to play with as a child on the beaches of Finnøya.”*

Indeed, Gjertrud Hals compares the shell to an organic membrane – at the same time protecting, fragile, fatal and liberating as… ”Premature fracture of many fragile protective shells or membranes means almost immediate death or destruction. On the other hand, a cleavage at the right moment may signify life liberating itself or even an idea or thought breaking forth and materializing itself in creativity”. With ULTIMA, the artist seems to approach, conceptually and technically, the fascinating ambiguity between fragility and force, art and death.

Some artists feel so rooted in their home region that it becomes an integrated part of their life and art, as organically inseparable from them as an arm, as vital as air. In the remarkable portrait movie Black Sun, Gjertrud Hals tells the gruesome story of how the little island Finnøya on the North West coast of Norway lost half of its population in one single afternoon: Thirteen people drowned during a sudden storm while trying to reach the church on a neighbouring island. This tragic event happened more than a hundred years ago, but it never lost its ambiguous power of terror and excitement to Hals, who was born on the island in 1948. “As a child, I loved stories about shipwrecks and accidents at sea. People who stayed alive on reefs and islets … or who had raised lots of children, for instance, and then lost them one by one. It sounds weird to say I loved it, but it was in a childlike manner. Joy mixed with terror. In those days we had no horror movies. We only had these stories.” (Black Sun, movie). Gjertrud Hals’ upbringing on the little island of Finnøya is profoundly anchored in her art and heart, and her relationship to the region’s nature and culture is deep and complex. So is her inspiration from the Nordic mythology, in which she sees a parallel to everyday life and culture.

Trained in the art of tapestry-weaving in the 1970’s, Gjertrud Hals’ interest in feminism and women’s culture associates her with the new Polish wave of women artists exploring the sculptural potential of textile, such as Claire Zeisler and Magdalena Abakanowicz. The word fiber art appeared in the United States in the 1960’s, and the first fiber art exhibition (“Woven Forms”) took place in 1963 in New York at the Museum of Contemporary Crafts. Previously, this style had been referred to as “off-loom”, and it is the process of binding elements together which comes from weaving that is the common denominator of fiber art.

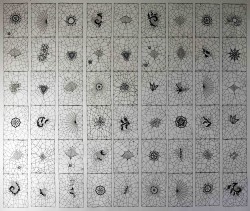

Connecting and binding together does indeed characterize Gjertrud Hals’ art, both literately and symbolically. Many of her works are grid structures made of cotton and linen crochets covered with paper pulp. Often strange little objects, objets trouvés, such as animal skeletons and feathers are added alongside with plastic capsules or embroideries from India or made by her grandmother, such as in the work FENRIS. They look a bit like the kind of “treasures” children find. The poetic dimension is further enhanced by the introduction of fragmentized words or letters, delicately appearing through the grid structures before vanishing again. Like a spider’s web, these weavings seem to capture the traces of life as time goes by. Like small micro-cosmoses, inspired by mythological story-telling and children’s worlds, Gjertrud Hals’ works seem to possess their own laws and logics, moving somewhere between delicate neatness and unrestrained inspiration. In the words of the artist, they propose a reflection “… on the relationship between nature and culture, in which the lives of modern humans are moving between chaos and order. Forces of nature and war create chaos, after which a new order is elaborated, always both the same and a little bit different than the previous. “

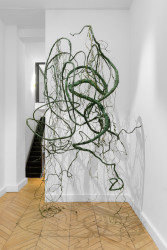

Gjertrud Hals works tirelessly, always seeking out new experiences. She has constantly explored new techniques, as she weaves, knits, casts, sprays and cuts her way through various materials, mostly natural fibres such as flax, paper, cotton, roots and plants that she elaborates during physical and time-consuming sessions. Her focus on natural fibres comes from her frequent travels to Japan, where she admires the ancient Shinto temples and learns to make paper. The Japanese word kami actually means both paper and for God, and it is the discovery of Japan’s old nature-worshipping religion, Shintoism, that puts nature at the heart of Gjertrud Hals’ work. For her, nature is not just an inspiration, but small pieces of natural life that she draws into her works in a direct manner, using roots, lichen and branches, as in the works PAIR and IRMIN: “With all that is happening in the world today, it feels right to focus on a small segment by conserving a small part of it. It reminds me of my collections of shells and insects from my childhood. It has always given me great pleasure to create order out of chaos.”*

It is also Shintoism that has opened her eyes for Norse mythology. She is struck by the feeling that so many things in today’s culture are rooted in these stories.

In the documentary Black Sun, the artist explains her spiritual approach to art and techniques, “Over the past 25 years, I’ve had a fling with Zen Buddhism. It focuses on technique but not for show. It’s a continued technical exercise. You should exercise so much that you forget the technique. And, in the end, yourself … Zen Buddhism is very down to earth. It’s about getting in touch with your inner child, and that reminds me of things I know from way back in my culture … my background … Christianity … and the essence of the New Testament. Several times, in the Gospels of Matthew and Mark, Jesus says that if you don’t become a child again, you’re not allowed into the kingdom of heaven. In that way, there is something in common … this simple down-to-earth mysticism. You can’t get there by keeping a safe distance. You must get into to it, take part in it.” (Black Sun, movie)

It is all about finding your inner child … getting into it, forgetting to keep a safe distance, being ALL IN, like a child – shipwrecks, spiders’ webs, snakes, animal skeletons and all. Chaos and order. Joy mixed with terror. Combining big and small, high and low, Gjertrud Hals mixes auto-biographical and feminist themes with legendary story-telling, folk art and fine art, profane and sacred … a simple down-to-earth mysticism, as she calls it, that beckons the child in us all.

*Tove Lande, ”Delicate Pillars. Weighty Threads.”In: Gjertrud Hals, Søjlens Letthet. Trådens Tyngde, Kunstmuseet KUBE 2008, pp. 75

*Gjertrud Hals in Tove Lande, “Delicate Pillars. Weighty Threads” in Gjertrud Hals, Søjlens Letthet. Trådens Tyngde, Kunstmuseet KUBE, 2008, pp. 77

- GJERTRUD HALS – ULTIMA

- Read more

The vessel is an ancient form in which we find the principles of both containment and protection – two of the fundamentals of life. Premature fracture of many fragile protective shells or membranes means almost immediate death or destruction. On the other hand, a cleavage at the right moment may signify life liberating itself or […]